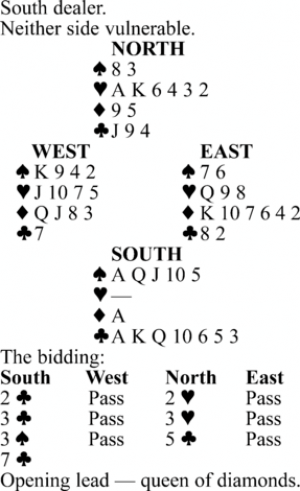

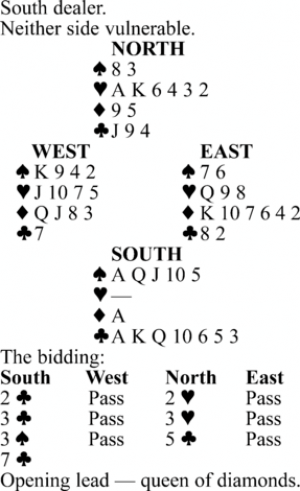

In the present case, for example, South didn’t know whether his partner had the king of spades but decided to bid seven anyway. He reasoned that even if North lacked the king, there might be alternative chances for 13 tricks, with a spade finesse still available as a last resort. South then proceeded to demonstrate that his assessment of the prospects was correct.

After winning the diamond lead, he led the five of clubs to the jack, cashed the A-K of hearts, discarding two spades, then ruffed a heart with the 10. When both opponents followed suit to the three heart leads, the grand slam became a certainty.

Declarer next led the six of clubs to the nine and ruffed another heart with the queen, establishing dummy’s two remaining hearts. The carefully preserved three of clubs was then led to dummy’s four, the two hearts were cashed, providing two more spade discards, and the grand slam was home.

By fully utilizing dummy’s heart length and three club entries, declarer thus assured the grand slam if the hearts were divided 4-3 and the clubs 2-1.

This, combined with the spade finesse available if the hearts or clubs were unfavorably divided, gave him better than a 2-to-1 chance to make the contract.

In the present case, for example, South didn’t know whether his partner had the king of spades but decided to bid seven anyway. He reasoned that even if North lacked the king, there might be alternative chances for 13 tricks, with a spade finesse still available as a last resort. South then proceeded to demonstrate that his assessment of the prospects was correct.

After winning the diamond lead, he led the five of clubs to the jack, cashed the A-K of hearts, discarding two spades, then ruffed a heart with the 10. When both opponents followed suit to the three heart leads, the grand slam became a certainty.

Declarer next led the six of clubs to the nine and ruffed another heart with the queen, establishing dummy’s two remaining hearts. The carefully preserved three of clubs was then led to dummy’s four, the two hearts were cashed, providing two more spade discards, and the grand slam was home.

By fully utilizing dummy’s heart length and three club entries, declarer thus assured the grand slam if the hearts were divided 4-3 and the clubs 2-1.

This, combined with the spade finesse available if the hearts or clubs were unfavorably divided, gave him better than a 2-to-1 chance to make the contract. Bridge: When to bid a Grand Slam By Steve Becker

Source: Tucson.com

As a rule, a grand slam should not be undertaken unless the chances in favor of making it are at least 2-to-1. These odds come from comparing what can be gained from making the grand slam — an additional 500 or 750 points, depending on vulnerability — to what can be lost — approximately 1,000 or 1,500 points.

It follows that bidding a grand slam that depends on a finesse — a 50-50 chance — is in the long run a losing proposition.

In the present case, for example, South didn’t know whether his partner had the king of spades but decided to bid seven anyway. He reasoned that even if North lacked the king, there might be alternative chances for 13 tricks, with a spade finesse still available as a last resort. South then proceeded to demonstrate that his assessment of the prospects was correct.

After winning the diamond lead, he led the five of clubs to the jack, cashed the A-K of hearts, discarding two spades, then ruffed a heart with the 10. When both opponents followed suit to the three heart leads, the grand slam became a certainty.

Declarer next led the six of clubs to the nine and ruffed another heart with the queen, establishing dummy’s two remaining hearts. The carefully preserved three of clubs was then led to dummy’s four, the two hearts were cashed, providing two more spade discards, and the grand slam was home.

By fully utilizing dummy’s heart length and three club entries, declarer thus assured the grand slam if the hearts were divided 4-3 and the clubs 2-1.

This, combined with the spade finesse available if the hearts or clubs were unfavorably divided, gave him better than a 2-to-1 chance to make the contract.

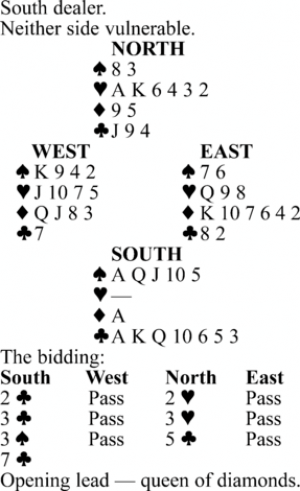

In the present case, for example, South didn’t know whether his partner had the king of spades but decided to bid seven anyway. He reasoned that even if North lacked the king, there might be alternative chances for 13 tricks, with a spade finesse still available as a last resort. South then proceeded to demonstrate that his assessment of the prospects was correct.

After winning the diamond lead, he led the five of clubs to the jack, cashed the A-K of hearts, discarding two spades, then ruffed a heart with the 10. When both opponents followed suit to the three heart leads, the grand slam became a certainty.

Declarer next led the six of clubs to the nine and ruffed another heart with the queen, establishing dummy’s two remaining hearts. The carefully preserved three of clubs was then led to dummy’s four, the two hearts were cashed, providing two more spade discards, and the grand slam was home.

By fully utilizing dummy’s heart length and three club entries, declarer thus assured the grand slam if the hearts were divided 4-3 and the clubs 2-1.

This, combined with the spade finesse available if the hearts or clubs were unfavorably divided, gave him better than a 2-to-1 chance to make the contract.

In the present case, for example, South didn’t know whether his partner had the king of spades but decided to bid seven anyway. He reasoned that even if North lacked the king, there might be alternative chances for 13 tricks, with a spade finesse still available as a last resort. South then proceeded to demonstrate that his assessment of the prospects was correct.

After winning the diamond lead, he led the five of clubs to the jack, cashed the A-K of hearts, discarding two spades, then ruffed a heart with the 10. When both opponents followed suit to the three heart leads, the grand slam became a certainty.

Declarer next led the six of clubs to the nine and ruffed another heart with the queen, establishing dummy’s two remaining hearts. The carefully preserved three of clubs was then led to dummy’s four, the two hearts were cashed, providing two more spade discards, and the grand slam was home.

By fully utilizing dummy’s heart length and three club entries, declarer thus assured the grand slam if the hearts were divided 4-3 and the clubs 2-1.

This, combined with the spade finesse available if the hearts or clubs were unfavorably divided, gave him better than a 2-to-1 chance to make the contract.

In the present case, for example, South didn’t know whether his partner had the king of spades but decided to bid seven anyway. He reasoned that even if North lacked the king, there might be alternative chances for 13 tricks, with a spade finesse still available as a last resort. South then proceeded to demonstrate that his assessment of the prospects was correct.

After winning the diamond lead, he led the five of clubs to the jack, cashed the A-K of hearts, discarding two spades, then ruffed a heart with the 10. When both opponents followed suit to the three heart leads, the grand slam became a certainty.

Declarer next led the six of clubs to the nine and ruffed another heart with the queen, establishing dummy’s two remaining hearts. The carefully preserved three of clubs was then led to dummy’s four, the two hearts were cashed, providing two more spade discards, and the grand slam was home.

By fully utilizing dummy’s heart length and three club entries, declarer thus assured the grand slam if the hearts were divided 4-3 and the clubs 2-1.

This, combined with the spade finesse available if the hearts or clubs were unfavorably divided, gave him better than a 2-to-1 chance to make the contract.