When the experts play bridge, the cards themselves represent only about fifty percent of any hand’s value. The other fifty percent is psychology. In this tight spot, Burnstone made full use of his knowledge of his opponents’ weaknesses. He knew that Messrs. Lightner and Culbertson are among the most nervous players in bridge. Ely, especially, hates to have to wait. When, as in this case, he is going to be dummy, he fidgets and frets until the opening lead is made. Then he flings down his hand, without even bothering to separate the suits, and races away from the table. He can’t stand the suspense of watching the hand played.

Realizing that the championship might well depend on his opening lead, Dave Burnstone decided to take his time. Very deliberately he reached into his pocket and pulled out a piece of chewing gum. He carefully unwrapped it, put it slowly into his mouth and gave a tentative chew. By this time Ted Lightner was actually squirming in his seat. Ely was beside himself with impatience. But still Burnstone couldn’t decide what to lead. And, in any event, he couldn’t lead until he had disposed of the chewing-gum wrapper. So he threw it down on the table.

Like a flash Culbertson threw down his dummy hand. An instant later he realized his error and hastily scooped up the cards It was too late. Capitalizing on his unexpected look at the dummy, Burnstone made the lead which set the hand. Small things often influence the outcome of major tournaments. A bottle of Coke was a big factor in the winning of the National Match-Point Team-of-Four Championship at Atlantic City, New Jersey, last year.

A Finesse or a Prayer?

It happened in a crucial hand on which I had to guess whether to finesse for the king of trumps or to play my ace and hope for the king to fall. There were only three trumps out and I had no way to guess how they were split. The percentage favors a finesse, but percentages are not infalible. I led a low trump from the dummy, and the player on my right played low —with just the proper air of nonchalance. I paused for a moment to see whether I had overlooked any sign which might give me a key to this move. The opponent on my left, waiting to play, hailed a passing waiter. “Will you get me a Coke, please?” he asked.

Then and there I knew that he had the missing king. No man orders a drink in the middle of a crucial hand unless he is trying to be too nonchalant. I played my ace and the king dropped. Our team won the tournament—by one quarter of a match point.

Hesitation during the play of a hand is perfectly ethical so long as you don’t overdo it. On the other hand, hesitation during the bidding is considered extremely bad form. It obviously reveals that the hand in question has some trick value or that there is a problem in it. This problem can be readily and accurately guessed by an expert partner. There is a classic bridge story involving Charlie Goren, one of the country’s top players.

In a local tournament several years ago Goren drew as his partner a somewhat inexpert old lady. Charlie dealt and bid one club. The opponent on his left overcalled with one spade. The old lady hesitated and finally passed. Goren then bid two clubs, which was promptly overcalled with two spades. This time the old lady paused even longer before passing. Goren finally got the contract for three clubs. When the old lady’s hand went own, it contained little trick value.

My.” remarked Goren. “That second hesitation certainly was an overbid.”

As chairman of the Committee on Ethics of the American Contract Bridge League, I can vouch for the fact that unethical conduct is practically unheard of at national tournaments. Occasionally, unwittingly, a player gets a glimpse of an opponent’s hand. Some players, even good ones, hold their cards in such a fashion as to make it impossible for them not to be seen. The saying that “a peek is worth two finesses” is the greatest understatement in bridge. But peekers quickly become known and are dealt with then and there by the other players.

I remember one local tournament when I was paired with a most charming lady. After the first couple of hands, it became obvious that one of our opponents was intentionally peeking. After the fourth or fifth deal as his eye started roving toward my partner’s hand, she turned to him with her sweetest smile and said, “I wish you wouldn’t look at my hand. I’m superstitious.”

At another small match I heard an expert turn to the player on his right and remark acidly; “Do you mind if I look at my hand first?”

Actually the Committee on Ethics has little work to do. Not so the committees on interpretation of the rules. I remember one incident in which an old lady asked the tournament chairman about the penalty for bidding out of turn. He informed her that she was barred from the bidding, regardless of the power of her hand. A couple of hours later the old lady came up to the chairman again, considerably agitated. “Please,” she asked humbly, “how long do I have to wait before I can bid again? I’ve had to keep quiet on some awfully good hands in the last hour.”

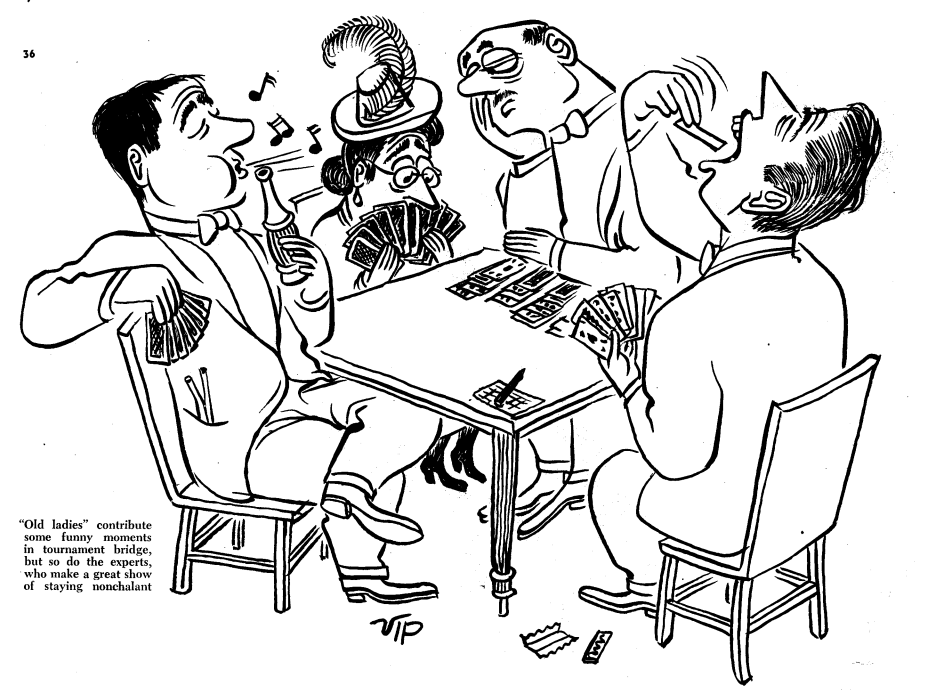

Of course, “old ladies” are not the only goats of the bridge table. But the experts always refer to duffers as “old ladies”—regardless of the sex or age of the offender. The old ladies get into so many bridge stories because all big tournaments have a few “open tables,” where the players of the community are invited to sit in. They don’t actually play in the tournament itself, but they often do get to play with the tournament players. Sometimes the quality of play at the open tables is excellent. But often it is not.

I recall a case in which a player was needed to fill out one of the pairs at an open table. The organizer of the tournament spotted an old lady among the spectators and asked her if she played cards. She nodded, so he took her over to a table where three other ladies were already seated. He introduced her all around and was about to leave when she called him back. “By the way,” she said, “which is my partner?”

He Knew Part of the Answer

Once George Kaufman, whose bridge is nearly as good as his dialogue, drew such a partner at an open table. He turned to her and asked: “Do you mind if I inquire when you learned to play?” And before she could answer, he added: “Oh, I know it was today. But I mean, what time today?”

Getting old ladies as opponents used to be the inevitable fate of two real-life experts named Dinkelspiel and Rabinowitz. On one such occasion, Rabinowitz opened the bidding with two spades. One of the old ladies opposing him looked up brightly and asked Dinkelspiel what his partner’s two spades meant. Mr. Rabinowitz left the table (in accordance with the rules) while Mr. Dinkelspiel explained. “Well, madam,” Dinkelspiel began, “two spades might mean five to five and a half Culbertson honor tricks. Or it might mean nine spades to the ace-king-queen and an outside ace— which is too strong for a three bid. Or . . .” And he continued for fully fifteen minutes explaining every possible combination of cards which might justify a Rabinowitz two bid.

Piling Confusion on Confusion

The poor old lady became increasingly confused as Dinkelspiel added possibility upon possibility. Finally he concluded: “But don’t you worry, madam. In this case Mr. Rabinowitz is just bidding a psychic. My hand is far too strong for him to have a legitimate two bid.”

Tournament players who live in the larger cities have a big edge over the experts whose homes are out of town. They have more chance to play against one another between tournaments and to learn the peculiarities and mannerisms of their opponents. This in turn tends to make the out-of-town players nervous in the big matches.

Not an inconsiderable factor in my winning of the World’s Individual Masters Tournament in 1941 was just such nervousness on the part of an otherwise excellent player from a small community. On the hand in question he was under terrific pressure. His partner was Charlie Lochridge, who was tied with me for the match lead. This was one of the few hands where Lochridge and I played directly against each other, so its result would greatly influence the tournament outcome. Because he was nervous, Mr. X played the hand unnecessarily badly. He went down one in a three-contract where four could easily have been made. At the end of the hand there was dead silence. Naturally my partner and I didn’t want to gloat. And Charlie Lochridge, one of the most considerate players among the masters, held his disappointment in perfect check. Into this tense silence, the still-confused Mr. X injected a question. “Could I have done better, partner?” And Mr. Lochridge, completely dead-pan, answered: “Well, sir, I think you could have played it double dummy to go down one more.”

Yes, even the experts make boners. At one championship I actually saw a player make seven hearts although he lacked the ace of trumps. What happened, of course, is that the opposition, playing carelessly because of a sure set, revoked. On the other hand the old ladies sometimes give the experts their comeuppance.

Messrs. Dinkelspiel and Rabinowitz used to delight in telling the following story: They were playing in a small tournament against the inevitable old ladies. Before the playing started, one of the old girls turned to Dinkelspiel and asked what system he played. “Chinese,” replied Dinkelspiel without cracking a smile. That seemed to satisfy the ladies and the bidding began.

“One spade,” said the first woman. “One no trump,” said Dinkelspiel. “Two spades,” said the second lady. “Two no trump,” said Rabinowitz. “Three clubs,” said the first woman. Everyone passed. When the hand was played, it became evident that Rabinowitz and Dinkelspiel had held a sure small slam in spades— unbid by them because, both having spades, each assumed that the other’s notrump bid was a psychic.

The Post Mortems Are Absorbing

But whether experts or “old ladies,” bridge players get completely wrapped up in the game. At a championship match in Asbury Park, New Jersey, the men’s and women’s tournaments were held at opposite ends of the gigantic convention hall. It happened that Howard Schenken, probably America’s best player, finished at one table before the next table was ready for him. So he wandered into the middle of the room, where he was promptly buttonholed by Helen Bonwit, a top woman player. She wanted his advice on a particularly difficult hand she had just played.

As they talked, they wandered about and eventually sat down to finish the post-mortem. It was fully ten minutes before anyone noticed that the seat Mr. Schenken occupied was right in the middle of the ladies’ room. But you don’t have to play bridge to enjoy it.

Until recently I used to play quite frequently at the New York Bridge Whist Club. For many years almost every evening that I played, a charming old gentleman would draw up a chair behind mine. He was the perfect kibitzer. He never gave an opinion. In fact, he never said a word. I grew to be very fond of him, and after the game we used to discuss everything from politics to morality. One evening I played a particularly difficult hand and went down. After it was over, the players got into a heated discussion as to how I should have played. The argument got hotter and hotter. Finally I turned to my kibitzing old gentleman—the first time I had asked his opinion about bridge in the many years he had sat watching. “Don’t you think I was right?” I asked. “Oh, I wouldn’t know,” he replied quickly. “You see, I don’t know how to play the game.”

THE END

When the experts play bridge, the cards themselves represent only about fifty percent of any hand’s value. The other fifty percent is psychology. In this tight spot, Burnstone made full use of his knowledge of his opponents’ weaknesses. He knew that Messrs. Lightner and Culbertson are among the most nervous players in bridge. Ely, especially, hates to have to wait. When, as in this case, he is going to be dummy, he fidgets and frets until the opening lead is made. Then he flings down his hand, without even bothering to separate the suits, and races away from the table. He can’t stand the suspense of watching the hand played.

Realizing that the championship might well depend on his opening lead, Dave Burnstone decided to take his time. Very deliberately he reached into his pocket and pulled out a piece of chewing gum. He carefully unwrapped it, put it slowly into his mouth and gave a tentative chew. By this time Ted Lightner was actually squirming in his seat. Ely was beside himself with impatience. But still Burnstone couldn’t decide what to lead. And, in any event, he couldn’t lead until he had disposed of the chewing-gum wrapper. So he threw it down on the table.

Like a flash Culbertson threw down his dummy hand. An instant later he realized his error and hastily scooped up the cards It was too late. Capitalizing on his unexpected look at the dummy, Burnstone made the lead which set the hand. Small things often influence the outcome of major tournaments. A bottle of Coke was a big factor in the winning of the National Match-Point Team-of-Four Championship at Atlantic City, New Jersey, last year.

A Finesse or a Prayer?

It happened in a crucial hand on which I had to guess whether to finesse for the king of trumps or to play my ace and hope for the king to fall. There were only three trumps out and I had no way to guess how they were split. The percentage favors a finesse, but percentages are not infalible. I led a low trump from the dummy, and the player on my right played low —with just the proper air of nonchalance. I paused for a moment to see whether I had overlooked any sign which might give me a key to this move. The opponent on my left, waiting to play, hailed a passing waiter. “Will you get me a Coke, please?” he asked.

Then and there I knew that he had the missing king. No man orders a drink in the middle of a crucial hand unless he is trying to be too nonchalant. I played my ace and the king dropped. Our team won the tournament—by one quarter of a match point.

Hesitation during the play of a hand is perfectly ethical so long as you don’t overdo it. On the other hand, hesitation during the bidding is considered extremely bad form. It obviously reveals that the hand in question has some trick value or that there is a problem in it. This problem can be readily and accurately guessed by an expert partner. There is a classic bridge story involving Charlie Goren, one of the country’s top players.

In a local tournament several years ago Goren drew as his partner a somewhat inexpert old lady. Charlie dealt and bid one club. The opponent on his left overcalled with one spade. The old lady hesitated and finally passed. Goren then bid two clubs, which was promptly overcalled with two spades. This time the old lady paused even longer before passing. Goren finally got the contract for three clubs. When the old lady’s hand went own, it contained little trick value.

My.” remarked Goren. “That second hesitation certainly was an overbid.”

As chairman of the Committee on Ethics of the American Contract Bridge League, I can vouch for the fact that unethical conduct is practically unheard of at national tournaments. Occasionally, unwittingly, a player gets a glimpse of an opponent’s hand. Some players, even good ones, hold their cards in such a fashion as to make it impossible for them not to be seen. The saying that “a peek is worth two finesses” is the greatest understatement in bridge. But peekers quickly become known and are dealt with then and there by the other players.

I remember one local tournament when I was paired with a most charming lady. After the first couple of hands, it became obvious that one of our opponents was intentionally peeking. After the fourth or fifth deal as his eye started roving toward my partner’s hand, she turned to him with her sweetest smile and said, “I wish you wouldn’t look at my hand. I’m superstitious.”

At another small match I heard an expert turn to the player on his right and remark acidly; “Do you mind if I look at my hand first?”

Actually the Committee on Ethics has little work to do. Not so the committees on interpretation of the rules. I remember one incident in which an old lady asked the tournament chairman about the penalty for bidding out of turn. He informed her that she was barred from the bidding, regardless of the power of her hand. A couple of hours later the old lady came up to the chairman again, considerably agitated. “Please,” she asked humbly, “how long do I have to wait before I can bid again? I’ve had to keep quiet on some awfully good hands in the last hour.”

Of course, “old ladies” are not the only goats of the bridge table. But the experts always refer to duffers as “old ladies”—regardless of the sex or age of the offender. The old ladies get into so many bridge stories because all big tournaments have a few “open tables,” where the players of the community are invited to sit in. They don’t actually play in the tournament itself, but they often do get to play with the tournament players. Sometimes the quality of play at the open tables is excellent. But often it is not.

I recall a case in which a player was needed to fill out one of the pairs at an open table. The organizer of the tournament spotted an old lady among the spectators and asked her if she played cards. She nodded, so he took her over to a table where three other ladies were already seated. He introduced her all around and was about to leave when she called him back. “By the way,” she said, “which is my partner?”

He Knew Part of the Answer

Once George Kaufman, whose bridge is nearly as good as his dialogue, drew such a partner at an open table. He turned to her and asked: “Do you mind if I inquire when you learned to play?” And before she could answer, he added: “Oh, I know it was today. But I mean, what time today?”

Getting old ladies as opponents used to be the inevitable fate of two real-life experts named Dinkelspiel and Rabinowitz. On one such occasion, Rabinowitz opened the bidding with two spades. One of the old ladies opposing him looked up brightly and asked Dinkelspiel what his partner’s two spades meant. Mr. Rabinowitz left the table (in accordance with the rules) while Mr. Dinkelspiel explained. “Well, madam,” Dinkelspiel began, “two spades might mean five to five and a half Culbertson honor tricks. Or it might mean nine spades to the ace-king-queen and an outside ace— which is too strong for a three bid. Or . . .” And he continued for fully fifteen minutes explaining every possible combination of cards which might justify a Rabinowitz two bid.

Piling Confusion on Confusion

The poor old lady became increasingly confused as Dinkelspiel added possibility upon possibility. Finally he concluded: “But don’t you worry, madam. In this case Mr. Rabinowitz is just bidding a psychic. My hand is far too strong for him to have a legitimate two bid.”

Tournament players who live in the larger cities have a big edge over the experts whose homes are out of town. They have more chance to play against one another between tournaments and to learn the peculiarities and mannerisms of their opponents. This in turn tends to make the out-of-town players nervous in the big matches.

Not an inconsiderable factor in my winning of the World’s Individual Masters Tournament in 1941 was just such nervousness on the part of an otherwise excellent player from a small community. On the hand in question he was under terrific pressure. His partner was Charlie Lochridge, who was tied with me for the match lead. This was one of the few hands where Lochridge and I played directly against each other, so its result would greatly influence the tournament outcome. Because he was nervous, Mr. X played the hand unnecessarily badly. He went down one in a three-contract where four could easily have been made. At the end of the hand there was dead silence. Naturally my partner and I didn’t want to gloat. And Charlie Lochridge, one of the most considerate players among the masters, held his disappointment in perfect check. Into this tense silence, the still-confused Mr. X injected a question. “Could I have done better, partner?” And Mr. Lochridge, completely dead-pan, answered: “Well, sir, I think you could have played it double dummy to go down one more.”

Yes, even the experts make boners. At one championship I actually saw a player make seven hearts although he lacked the ace of trumps. What happened, of course, is that the opposition, playing carelessly because of a sure set, revoked. On the other hand the old ladies sometimes give the experts their comeuppance.

Messrs. Dinkelspiel and Rabinowitz used to delight in telling the following story: They were playing in a small tournament against the inevitable old ladies. Before the playing started, one of the old girls turned to Dinkelspiel and asked what system he played. “Chinese,” replied Dinkelspiel without cracking a smile. That seemed to satisfy the ladies and the bidding began.

“One spade,” said the first woman. “One no trump,” said Dinkelspiel. “Two spades,” said the second lady. “Two no trump,” said Rabinowitz. “Three clubs,” said the first woman. Everyone passed. When the hand was played, it became evident that Rabinowitz and Dinkelspiel had held a sure small slam in spades— unbid by them because, both having spades, each assumed that the other’s notrump bid was a psychic.

The Post Mortems Are Absorbing

But whether experts or “old ladies,” bridge players get completely wrapped up in the game. At a championship match in Asbury Park, New Jersey, the men’s and women’s tournaments were held at opposite ends of the gigantic convention hall. It happened that Howard Schenken, probably America’s best player, finished at one table before the next table was ready for him. So he wandered into the middle of the room, where he was promptly buttonholed by Helen Bonwit, a top woman player. She wanted his advice on a particularly difficult hand she had just played.

As they talked, they wandered about and eventually sat down to finish the post-mortem. It was fully ten minutes before anyone noticed that the seat Mr. Schenken occupied was right in the middle of the ladies’ room. But you don’t have to play bridge to enjoy it.

Until recently I used to play quite frequently at the New York Bridge Whist Club. For many years almost every evening that I played, a charming old gentleman would draw up a chair behind mine. He was the perfect kibitzer. He never gave an opinion. In fact, he never said a word. I grew to be very fond of him, and after the game we used to discuss everything from politics to morality. One evening I played a particularly difficult hand and went down. After it was over, the players got into a heated discussion as to how I should have played. The argument got hotter and hotter. Finally I turned to my kibitzing old gentleman—the first time I had asked his opinion about bridge in the many years he had sat watching. “Don’t you think I was right?” I asked. “Oh, I wouldn’t know,” he replied quickly. “You see, I don’t know how to play the game.”

THE END

Lee Hazen: Wins & Runners-up

Wins

- North American Bridge Championships (12)

- Masters Individual (1) 1941

- Wernher Open Pairs (1) 1945

- Vanderbilt (4) 1939, 1942, 1949, 1958

- Marcus Cup (1) 1953

- Reisinger (2) 1945, 1949

- Spingold (3) 1942, 1947, 1955

Runners-up

- Bermuda Bowl (2) 1956, 1959

- North American Bridge Championships

- Masters Individual (1) 1940

- von Zedtwitz Life Master Pairs (1) 1946

- Vanderbilt (2) 1944, 1947

- Reisinger (2) 1941, 1942

- Spingold (2) 1945, 1958

Don’t forget to follow us @