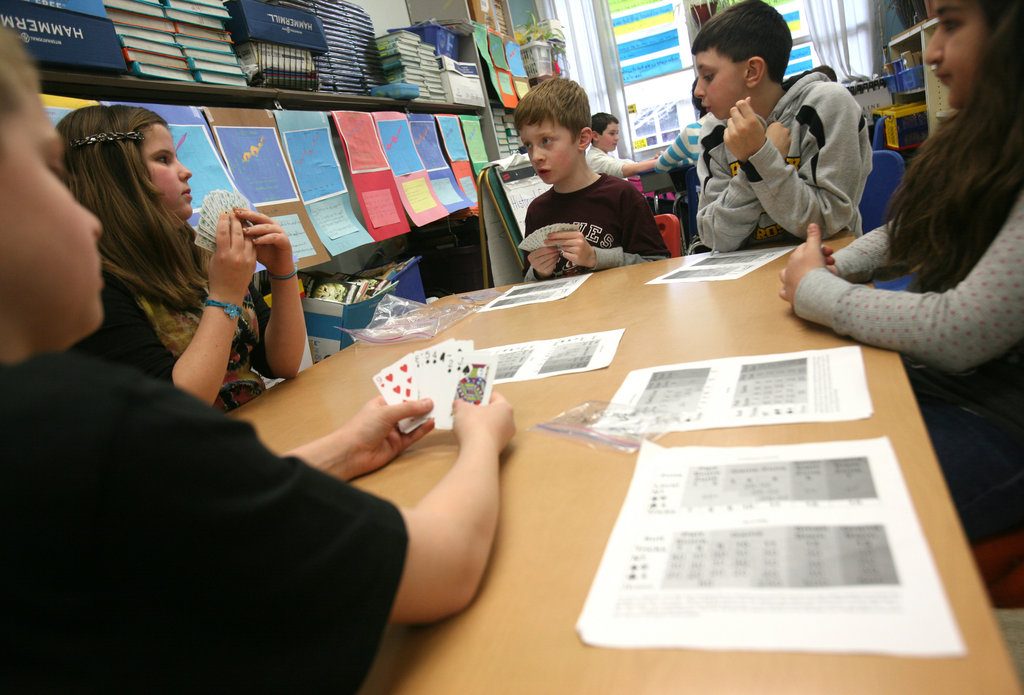

YORKTOWN HEIGHTS, N.Y. — Four bridge players stared down at their cards, trying to determine which team would play the role of the so-called declarer and dummy.

Then one of the four, Max Plati, 8, dissolved into laughter as he mouthed to the boy sitting across from him: “You’re the dummy!”

Their teacher, Eileen Crowley-Bloss, reminded her second-grade students at the Thomas Jefferson School that in bridge, the meaning of “dummy” is “silent partner.” Even more unfamiliar, though, may have been the students’ quiet play and earnest concentration, all without the involvement of an electronic device.

Chess is still the game of choice among educators, but bridge is catching on at a growing number of schools, community leagues and recreational centers across the nation, many of which see the card game as offering similar mental benefits to those of chess, but with a social component.

The Lakeland district in this northern Westchester County town began teaching bridge this year as a way to both reinforce math and problem-solving skills and to socialize a generation of children raised on solitary pastimes like playing video games and listening to iPods. Now kindergartners here learn to sort suits and high and low numbers, while older students play in bridge clubs and compete online in virtual tournaments.

Their efforts to promote bridge among students have helped revive a game that peaked in popularity in the years after World War II, and have redefined it from a leisurely pastime for the elderly to a game fit for interscholastic contests in which young players vie for trophies, scholarships and bragging rights.

In 2009, a 9-year-old Georgia boy, Richard Jeng, became the youngest player to earn the rank of life master from the American Contract Bridge League, the nation’s largest bridge organization; the average age of its 165,000 members is 67. Three hundred top junior players are expected to compete in the fourth annual Youth North American Bridge Championships in Toronto in July, while hundreds more will play in local tournaments this year.

“To see seventh and eighth graders sitting and concentrating for three hours, it never happens except in bridge,” said Bud Brewer, whose nonprofit group, Reno Youth Bridge, held a tournament in April after teaching the game to 160 students in 14 public middle schools and three private schools in Reno and Sparks, Nev.

Similar youth bridge programs have cropped up in more than a dozen other cities, including Atlanta; Raleigh, N.C.; Pensacola, Fla.; Phoenix; and Honolulu. Atlanta Junior Bridge, which was started by bridge players in 2006, has taught the game to 1,700 students in after-school classes and summer camps, and this year it developed a math-based bridge curriculum that is being taught in schools like Buford Middle in the Atlanta suburbs.

Leslie Markes, an eighth-grade math teacher at Buford, recalled that puzzled students asked at first whether they were going to build bridges. Now the 30-minute bridge class is so popular that she has to turn away students. “We wanted to teach them math in a new way,” she said. “But we didn’t bill it as ‘come take an extra math class.’ ”

Bridge is a challenging game even for adults, requiring strategy and the memorization of complex rules. Yet evidence of its academic benefits is still largely anecdotal. A 2005 study by Christopher C. Shaw, a retired business professor and bridge player, found that a group of bridge-playing fifth-grade students in Carlinville, Ill., made larger gains on standardized tests than their classmates, but academic scholars have called these findings limited and preliminary. Mr. Shaw is conducting a similar bridge study with students in Mount Pleasant, Iowa.

“My intuition says bridge is a really good tool to develop critical thinking and inferential reasoning, plus it gives them a lifetime recreational skill,” Dr. Shaw said.

Bill Gates and Warren Buffett were persuaded by their own experience as bridge players to pledge $1 million in 2005 to promote bridge in schools.

The money was used to help create School Bridge League, a program that generated interest in the game through introductory classes, online tournaments and presentations at teacher conferences. The efforts fell short, in part because schools were cutting programs, not adding them, and students found it hard to learn the game — let alone become regulars — with just a handful of lessons.

The money was used to help create School Bridge League, a program that generated interest in the game through introductory classes, online tournaments and presentations at teacher conferences. The efforts fell short, in part because schools were cutting programs, not adding them, and students found it hard to learn the game — let alone become regulars — with just a handful of lessons.

School Bridge League’s founders eventually returned $400,000 to Mr. Gates and Mr. Buffett in 2010. Nevertheless, they tried again last summer, reorganizing the program under Enith Berg, a retired teacher and bridge player. They are trying to build more comprehensive programs in fewer districts — Lakeland is one — by starting with younger children and a pared-down version of the game, known as mini-bridge.

This time, the program is being run on a shoestring budget with donations from, among others, Jon Sandelman, a hedge-fund financier, and David Barger, chief executive of JetBlue, who donated 25 free airline tickets, some of which have been used as prizes in tournaments.

In New York City this year, School Bridge League helped introduce the game at the Anderson School, a citywide school for gifted and talented students that teaches bridge to third graders. The school also created an elective class for middle school students, and held a family bridge night in March. Another school, Midtown West, has formed a bridge club for fourth and fifth graders and a bridge group for parents.

“Unlike chess, it forces students to collaborate together,” said Dean Ketchum, the Midtown West principal. “And we’re providing families with an academic activity they can share for a lifetime.”

Even schools where money is tight are finding a way to teach bridge. The Orange Township school district in New Jersey started bridge clubs for 30 students at two elementary schools last year after a gifted program offering bridge lessons was eliminated in budget cuts. Next fall, the district plans to expand the bridge clubs to two more schools in response to growing interest.

George Stone, the superintendent of the 6,200-student Lakeland district, said he decided to introduce bridge in five elementary schools after learning the benefits from Ms. Berg, who is also his neighbor. He said he hoped to expand it to the middle and high schools. The School Bridge League, which pays for the program, has spent about $5,000 on cards, materials and bridge instructors for the students and staff.

Dr. Stone is not a player himself. “I tried to learn, and I wasn’t as successful as our students,” he said. “Between the rules and memorization and thinking skills and logic and teamwork, it’s astounding the kids can adapt to it so quickly.”

In Ms. Crowley-Bloss’s class recently, the second graders sat at desks arranged in fours and calculated points from their cards by writing out addition problems. Then the games began. Max, glancing at his partner, threw down an ace to win a trick.

“I just like winning,” said Max, who also plays chess. “Bridge is more fun than chess because you have a partner to help you if you’re in a tough situation.”

At the nearby Benjamin Franklin School, a fifth-grade class was reviewing bridge rules and vocabulary from a PowerPoint projection. One question: When someone gets a higher card than you, what do you call that? (Answer: Trump.)

“Think Donald,” the teacher, Annamarie Conte, told the students before they gathered up their cards and sat down to play.

“It kind of teaches us math, but I like it better than math,” said Jack Schwerner, 10, who ranked bridge ahead of video games, but behind football.

Patricia McIlvenny, the principal, said the lessons in teamwork and cooperation learned around the bridge table were as important as the academic ones.

“You can’t text your partner your strategy,” she said. “You actually have to put down your cellphone and interact around a table. It’s reintroducing a lot of social skills that have been lost.”

Don’t forget to follow us @