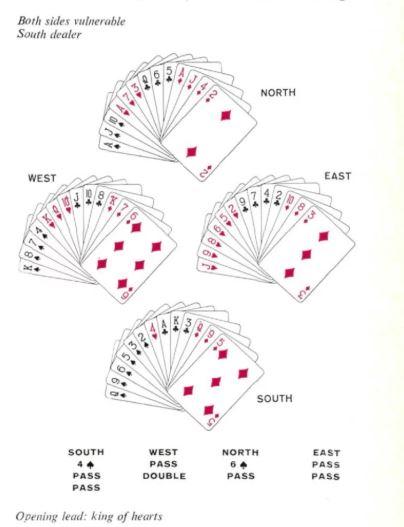

“The bidding in this deal —particularly Jackie’s—was not what is generally known as conventional. To make things easier for my readers I will state forthwith what was revealed to me only at long last—that Jackie had somehow or other mixed up her black cards, and what she took to be the ace and king of spades turned out to be the ace and king of clubs!

“I spread my hand, and after one look, Jackie jumped six inches straight up! What was the spade ace doing there when she had it? To my horror, I saw her amazement change to consternation and then saw her pick out two cards and transfer them hastily to the other end of her hand.

“But now that Jackie had found the explanation to what had appeared an eerie matter, she regained her aplomb, and soon my eyes were popping to the finest performance of even her distinguished career. She took the heart king with the ace and, perhaps because she loves to ruff, ruffed a heart. She also loves to finesse, so she promptly finessed for the spade king. When my 10 held she was so pleased that she looked on East’s failure to follow suit as merely another ‘detail.’ A second heart ruff and a second spade finesse, to the jack, reduced her to the queen-9 of trumps.

“It is no part of my intention to claim that my wife takes smother plays in her stride. It is worth observing that she could have cashed the spade ace, cleaned up the clubs, then thrown West in with the spade king, forcing a diamond return from the king. But, as compared with that humdrum routine line, Jackie’s technique was a work of art.

“The bidding in this deal —particularly Jackie’s—was not what is generally known as conventional. To make things easier for my readers I will state forthwith what was revealed to me only at long last—that Jackie had somehow or other mixed up her black cards, and what she took to be the ace and king of spades turned out to be the ace and king of clubs!

“I spread my hand, and after one look, Jackie jumped six inches straight up! What was the spade ace doing there when she had it? To my horror, I saw her amazement change to consternation and then saw her pick out two cards and transfer them hastily to the other end of her hand.

“But now that Jackie had found the explanation to what had appeared an eerie matter, she regained her aplomb, and soon my eyes were popping to the finest performance of even her distinguished career. She took the heart king with the ace and, perhaps because she loves to ruff, ruffed a heart. She also loves to finesse, so she promptly finessed for the spade king. When my 10 held she was so pleased that she looked on East’s failure to follow suit as merely another ‘detail.’ A second heart ruff and a second spade finesse, to the jack, reduced her to the queen-9 of trumps.

“It is no part of my intention to claim that my wife takes smother plays in her stride. It is worth observing that she could have cashed the spade ace, cleaned up the clubs, then thrown West in with the spade king, forcing a diamond return from the king. But, as compared with that humdrum routine line, Jackie’s technique was a work of art.

“She did not cash the spade ace. She cashed the clubs, ending in her hand.”

Moyse’s story goes on but suffice it to say that Jackie next led the queen of diamonds, which was covered by the king and won with the ace. Next came the jack of diamonds and a low diamond. East was in and no matter what he returned, West was unable to make a trick with his guarded spade king after Jackie had trumped, even though dummy’s ace was alone.

When the hand was done, Sonny raved: “A smother play, a smother play. Why, Baby, do you know that there aren’t more than a couple of hundred players in the country who can execute one of those?”

It was then that Jackie explained about having mistaken the ace and king of clubs for the ace and king of spades, and apologized for her opening bid. “Next time, I’ll bring my glasses,” she said, “and then I’ll play a lot better.”

That ended the rubber and the story. No doubt I have done less than justice to the Moysian flavor by quoting from only a part of one of his many Jackie stories. But perhaps some day soon they will all be collected into a book. I for one will want a copy. Autographed by Jackie, of course.